Who's Next in Context

So far, I've written mainly reviews of new CDs. I have decided to do something completely different this time around. In this review, I am going to take a look at one of the greatest, most well-known rock albums ever recorded, Who's Next by the Who. However, since I am an avowed, card-carrying, Who fanatic, I do not think a straight "review" of the album will be fair, since I am biased. Also, the whys and what’s of this album have already been explored in tons of other reviews written by others. I do not feel it necessary to rehash or rewrite what they’ve already written. So, what I will do for this review is use this album as a springboard to outline and explain the band and the things that make them unique.

It's All About Attitude

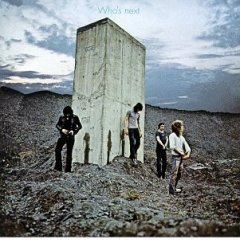

Start with the cover. One of the primary traits of The Who becomes evident, just from a glance. They are irreverent. They are crude. They are rude. And they are funny. The Who's Next album was released in 1971, when the film 2001 was still vividly in the minds of the public. In that film there is a huge alien monolith, which, although ambiguous in the movie, seems to serve the purpose of guiding and inspiring mankind from its "birth" through its momentous achievement of space travel and beyond. According to Pete Townshend, guitarist, songwriter and main mouthpiece of the band, the cover was influenced by the movie. The story told is that the band happened to have a photographer with them as they were driving between gigs in England and passed a slagheap. The photographer saw the huge concrete slabs sticking up out of the heap (they are put there to keep the slag heap from "shifting") and thought it the perfect backdrop for a photo shoot. He convinced the band to stop and pose for photos. Outtakes from the photo shoot reveal that it started out as expected, with the band striking poses similar to those seen in the movie 2001, bowing down and worshipping the stone slab. As the shoot progresses, the members of the band appear more and more restless and upset, until the photo used for the cover emerges. And the band shows just what they think about the "guiding force of mankind" by what they have obviously just finished doing on the monolith. According to Townshend, the statement was intentional, and, in fact, the "stains" on the monolith are real too. It may be strange that fanatics love a band because of their irreverent and rude attitude, especially when the band is just as likely to take out their aggression on those same fans. For example, after hearing one too many screams for Magic Bus at a concert in 1977, Townshend responded with, "there's a guitar up here on stage, if one of you big mouth little gits want to come up here and fucking take it off me." There is a lighter side to the attitude, however, as evidenced by the fact that immediately after delivering the diatribe the band played Magic Bus.

What About The Music?

Ultimately, any band must be judged on the quality of the music. The Who are no different in that respect. Their music, however, is very different from most other "conventional" rock 'n' roll. The instrumentation used by the Who is no different than that of any other band, guitar, bass, drums, keyboard, and voice, but the role each instrument plays in relation to the other instruments is very different. As the very first note of this album begins that difference hits the listener like a slap in the face.

The song Baba O'Riley opens with a wash of synth. Playing a single-note pattern in repetition, it establishes a hypnotic, circular pattern before being joined by any other instrumentation. The first instrument to join in with the synth is Pete Townshend's piano. Simply establishing the beat, the piano plays simple chords to accent the synth pattern. Next, Keith Moon's drums come thundering in, as they often do, and cements the beat of the song. Once that task is accomplished, John Entwistle's bass slides into the sound. Unlike his usual role in the Who's music, in this number Entwistle simply echoes the piano, solidifying and strengthening its sound. Roger Daltrey jumps into the song next, his vocals a barely contained scream as he sings the opening line, "Out here in the fields / We fought for our meals." Finally, after the first verse Pete Townshend's guitar slices into the song with blistering power chords.

Differing remarkably from the usual Who formula, during this number the piano, drums, bass, and guitar all fill out the song just keeping the beat, echoing the original piano part, and allow the synth track to carry the tune. Although, typical to Who formula, this song does contain a bridge in which all instrumentation alters. After a huge crescendo of power chords, every instrument, except the synth, drops out completely, while Townshend sings the line, "Don't cry, don't raise your eyes, its only teenage wasteland." From a listening standpoint, it seems as if the revelation in the bridge has freed the band, for when they power back in, the playing is louder, more forceful, and even has a few added accents which were absent prior to the bridge.

The song continues to build momentum with the band notching up with every note until the song reaches a crescendo, and everything changes. A violin, played by Dave Arbus, joins in at the last of the crescendo, as all the other instruments, except synth, fade away. The violin finds an alternate melody among the synth part and begins following it. As the other instruments join back into the song, in reverse order of how they exited, they also pick up the new melody, turning the end of the song into a synth-led, futuristic square dance. Several key elements to a fanatic's love of the band can be found in this song. In this song, for example, the band members play a simple "time keeping" role. However, even then, Keith Moon cannot help but throw in constant fills, rolls, and other bits of quickie drum pyrotechnics. Likewise, Entwistle throws in a few instances of fancy bass-work.

Bargain, the next song on the album, is different. It is formula Who all the way. The song opens with simple guitar strumming, with backwards guitar accompaniment. After a few bars of this, setting the chord progression and melodic foundation, everything breaks down. The drums roll in, followed by a tremendous explosion of sound from the rest of the band. As a single-note synth part trails along, marking the chord changes, the bass guitar carries the melody of the tune while the lead guitar accents the beats with power chords. Meanwhile, the drums fill in the space left between the bass melody and the guitar chords. Notice, especially, the bass drum work. Moon does not simply hit 'boom-space-boom-boom," he uses the bass as another tom and plays a spectacular pattern, "boom-space-roll-boom, boom-roll-space-boom." Amazingly enough, on top of this he also plays a spectacular series of fills concurrently on the rest of his kit. Overall, this is a stunning display of skill.

As stated above, the bass is the main melodic force within this song. It carries the tune, which is traditionally the role of the lead guitar. The bass swoops and bounces along. Listen to it especially during the bridge, as it is the sole instrument heard behind Townshend's voice as he sings, "I look around / I look at my face in the mirror / I know I'm worth nothing without you / and like one and one don't make two / one and one make one / I'm looking for that free ride to me / I'm looking for you." And to hear a perfect example of how The Who's sound is really defined by the bass and drums, listen to the bass/drum break immediately following the above vocals. Strummed acoustic guitar set the beat and present the chords in the deep background. A single-note synth pattern sweeps across the top of the music. It is, however, the space in between those two instruments where the song is really taking shape. The bass plays the melody, while the drums fill in the spaces left by the bass' fingerpicked sound. As the song reaches its conclusion, all the pieces start to break free. The guitar starts playing a choppy melody, the bass flies off in its own direction. The synth slides in and out of the music. The drums tie all this madness together with a bass drum roll. The song builds, and builds, until there is nothing left for it to do than just end, which it does.

Love Ain’t For Keeping shows another side of the band. Far from being a hard-rock showstopper like the track before, it is very close to being a real country number. This is a great example of the genius of the album’s producer, Glyn Johns, he knew there would be no way to top the performance contained in the previous number, so he shifted gears on the music entirely. This song is driven by a twin acoustic guitar attack. One acoustic guitar is strummed while the other is fingerpicked. The bass bubbles along underneath, playing an alternate melody. Because the rest of the instrumentation is already so busy, Moon uses the drums to simply keep time. Of course, saying Moon does anything with the drums "simply," is a bit of a misnomer, but this is one of his most conventional drum parts. On top of all this, Roger Daltrey sings the lyrics. The song contains some nice alliterations, but is otherwise lyrically unexceptional. This is a fun tune that effectively breaks the pattern and shifts the mood of the album thus far.

The next song on the album is the only one in the collection not written by Pete Townshend. John Entwistle’s My Wife is a funny song about a man on the run from his wife because “She thinks I’ve been with another woman.” When the truth was, “all I did was have a bit too much to drink / but I picked the wrong precinct / got picked up by the law and now I ain’t got time to think.” Bass guitar carries this tune. Because this song is written and sung by Entwistle, the band allows his bass to be the loudest instrument in the mix. For this number it acts as lead guitar. Keith Moon follows the bass line with a complicated pattern, throwing in fills whenever the mood strikes. In this number Townshend’s guitar is barely audible, reduced to playing time-keeping power chords in the background. A horn section, actually Entwistle himself overdubbed multiple times, appears at the end of each chorus to accent the beat, then disappears. This song totally turns the listeners typical expectations upside down. Earlier in the album, the band used the bass guitar as the main instrument in the tune, but always did so with the instrument slotted into its usual position in the mix. On this number, that has changed. The bass is in the space usually reserved for lead guitar, and the lead guitar has been shunted into the bass guitar position. The unusual sound field caused by this can be disconcerting to some listeners, but it does create an unusual, chilling atmosphere, which befits the dark humor of the material, a trademark of Entwistle-written songs.

Just as every song so far has been driven by a different instrument, guitar, bass, or synth, The Song Is Over is driven by piano. Piano, echoed by guitar, opens the tune. Townshend sings the first verse over this sparse accompaniment. For the chorus that follows, Daltrey takes over vocals and sings in front of the entire band. This is the case with the rest of the song too. Townshend and piano on verses, Daltrey with full band of choruses. This is a beautiful, uplifting tune about rediscovering yourself after losing the love of someone else.

Getting In Tune begins with a nice, quiet, elegant piano melody. Entwistle plays a light bass line behind the piano as embellishment. Daltrey begins the song with the chorus, singing it over this sparse arrangement. After the last line, however, the full band thunders in, with Keith Moon leading the charge. The bass guitar carries the tune, playing the melody, while the lead guitar marks the beat and throws in the occasional embellishment. The drums thunder through this track, pushing it forward.

Goin’ Mobile is a cute little ditty about life on the road. It opens as a cute little country tune, with acoustic guitar, bass and drums. Bass and guitar carry the tune with the drums keeping a complex, and heavy beat. After a few verses, the entire song changes, though. The acoustic guitar changes to an electric, fed through an ARP synth. Right after the introduction of this new, and incredible sounding, new “instrument,” the song flies of into the stratosphere. Townshend plays an incredible solo, the drums go wild, and bass begins swooping and zooming all over the soundscape. If you are a fan of guitar, this song is a must-hear, as no description can adequately describe either the sound or the ability displayed by the ARP-guitar and Townshend. Taking a guess, I would imagine that this song was written simply to show off the new technology of feeding a guitar through a synth. It works. The song is fun, and, even today, will cause your jaw to hit the floor in disbelief.

Behind Blue Eyes opens with the Who formula in reverse. Acoustic, fingerpicked guitar plays the melody, while bass marks the beat. On the first chorus, the song reverses. Bass takes over the melody, while the guitar switches from being fingerpicked to strummed, as it also takes over time keeping. The instrumentation continues switching through the choruses and verses of the song. Until, that is, the last chorus, when drums join in and the song becomes a heavy-rocker, before finally reverting back to the gentle tune it was in the beginning. This is a brilliant song of redemption and understanding, with Daltrey delivering one of his strongest vocal performances ever, and music that perfectly captures the conflicting emotions of sadness, and rage, studied in the lyrics. This song really highlights the Who’s skills as individual musicians, as collective musicians and as performers. Very few other bands could have pulled off the switch from delicate acoustic tune to heavy rocker in a single note as the Who does in this number. Also, very few bands contain the technical musical ability to play around, and with, each other the way Townshend and Entwistle do in the acoustic passages in this number. Once the heavy portion of this song starts, pay extra attention to Keith Moon. In what could have been a typical heavy-rock break, he ignores the places where a “typical” drummer would have placed fills and accents, performing his before or after the “typical” placement, and delivers an unusual and uncanny performance.

Won’t Get Fooled Again has earned its place as perhaps the greatest showcase of the Who’s tremendous talents. It is a warhorse of a song. Clocking in at nearly nine minutes, it runs the gamut of sounds and styles inherent in the delivery of the band. Opening with a tremendous power chord which fades into another of Townshend’s hypnotic synth patterns, it makes an immediate impact. The band thunders in and then goes silent allowing the drums to establish a beat before they all return to power through the song. The bass carries the tune, with Entwistle swooping and diving through the music as Townshend ingeniously keeps beat and deliver an unbelievable power-chord laden lead guitar line. After each chorus, Entwistle moves into a holding pattern, keeping the beat, allowing Townshend to deliver an amazing guitar break before returning to the next verse, where they reverse places again. Meanwhile the drums careen through the song, half keeping time, half delivering what could best be described as a drum solo. And through it all, buried deep in the background, the hypnotic synth line can still be heard. Over all the madness of the instrumentation, Daltrey delivers a powerful, growling vocal performance. His voice is angry and biting, as he yells his way through the lyrics, trying to be heard above the racket. The song gets a bit further out of control with each chorus, the guitar breaks becoming wilder and less restrained, the drums careening further and further away from any resemblance of keeping a beat and the bass swooping longer and louder. Then suddenly it all stops. After one last, crazy, guitar break the instruments drop out, leaving behind just the synth line. The synth continues alone for a time, flowing and bouncing in a trance inducing performance. Finally, the monotony of the synth is broken as Moon dives back into the song with a drum solo. Short and succinct, it is not as impressive a “solo” as the vast majority of his regular drum parts, but it suffices to reintroduce the band to the song. The band crashes back into the song at the end of Moon’s solo led by a blood chilling scream from Daltrey. They thrash through one final vocal line, “Meet the new boss / Same as the old boss,” before slashing through the finale of the song. The break has allowed the band to regain their composure. The end of the song is much less out of control than the song had grown by the time the instruments dropped out for the synth break. The song ends cold, the band delivering a few coordinated power chords before finally disappearing.

The Final Word

The question may still remain, what makes the Who different? The answer can be found by examining this album and studying its contents. The instrumentation that the Who used was ordinary, the same as any other band. However, the roles of the instruments were very different within the Who. The group plays with incredible power and ability. They interact with each other, musically, almost instinctively, providing a collective ability well above most other bands. The group is also innovative. In a recent interview Daltrey noted that the album Who’s Next was very experimental for its day and in fact, “it still sounds very innovative today, thirty years later.” The songwriting is strong, Townshend showing an uncanny ability to tap into the emotions and heartbreak of ordinary people in everyday situations and turn them into extraordinary lyrics. Overall, this album earns its reputation as one of the most distinctive and important rock albums ever recorded. It also is the perfect representation of the band that recorded it, and showcases, effectively, what makes the Who a unique and distinctive group.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home